Software engineering, like other trades, is something that can be done in many ways. Throughout the years people have established patterns and practices to help craft good software. One set of design principles we’ve been discussing is SOLID. Robert C. Martin coded the Interface Segregation Principle (ISP) which “I” represents.

Today’s post is fourth in a five part series. You can find the first parts here: Single Responsibility Principle, Open/Closed Principle, and Liskov Substitution Principle.

You will find code for today’s post on my GitHub page. I’ve split the code into two portions: before and after.

What is the Interface Segregation Principle?

Interface segregation principle is defined: “…no client should be forced to depend on methods it does not use.” – Agile Software Development; Robert C. Martin; Prentice Hall, 2003. On it’s head that statement could be interpreted many different directions yet at it’s core, it really is quite simple.

If we consider that another class is the “client” in this statement, it becomes a bit easier to break down. If the “interface” our class needs to implement is a base class or an interface, we can see that ISP is telling us that it shouldn’t have to implement things it won’t use.

How to violate the Interface Segregation Principle

The easiest way to determine if your code violates ISP is to see if you have any unimplemented methods or properties. If your completed code has throw new NotImplementedException() then you’re violating it. Simple as that. It’s one thing to stub in the methods when you first implement an interface since most code tools will stub the method in with that exception. It’s quite another to think you’re done but still have those in there.

You’ll find a perfect example of me violating this principle in the code for Open/Closed Principle. Look at the InMemoryEmployeeRepository.cs file and notice that I haven’t implemented SaveAsync.

Of course we can’t stop there. If a method has no return type (aka void), for example, you might simply leave the method declaration empty. That too is a violation of ISP.

Similarly if you have a property and you either return the default for value types or null for reference types while also having the setter do nothing we are once again looking at a violation of ISP.

Implementing Interface Segregation Principle, a practical example

Rather than just talking about what it is and how to violate it, I figure it is worth our while to explore a practical example. Let’s consider for the sake of our example a brick and mortar store that also has some sort of eCommerce integration. Since they have both a physical and digital presence they can accept payments in cash, check, credit card, PayPal, and online check.

For all intents and purposes we handle payments “the same” as one another. Over time as we introduce different payment methods we’ll bolt those onto the system. The problem this system may face, then, is that different payment types might not actually support all the same functions as one another.

Setting the stage

To begin, let’s explore the functions you might perform on payment: Authorize, Capture, Credit, Void. In “ye olden days” of programming we’d start out by creating an abstract base class for PaymentProcessorBase which defines all the methods and properties we might need. We’d then sub-class a different processor for each payment type such as CashPaymentProcessor, CreditCardPaymentProcessor, etc.

Next, we might have some sort of PaymentProcessorFactory that we pass in a PaymentItem and it returns an instance of a processor. Lastly, we attempt to run the particular action against that processor instance. This workflow has worked for years, it’s fine, it’s dandy. But it violates ISP.

I don’t want to go into too much detail for the “before” scenario so I invite you to look at the code and review the “Before” section. This code is ugly and I’m ok with that.

Breaking it down

One thing to note before we start digging is that implementing ISP should go hand-in-hand with single responsibility principle (SRP). Let’s look at the scenario we’re discussing. You *could* make a different concrete implementation for each action for a particular payment processor. For example, you could have a VoidableCreditCardProcessor. But why? The responsibility of a CreditCardProcessor is to run payment related actions on a payment, right? SRP allows us to have all the interfaces implemented there.

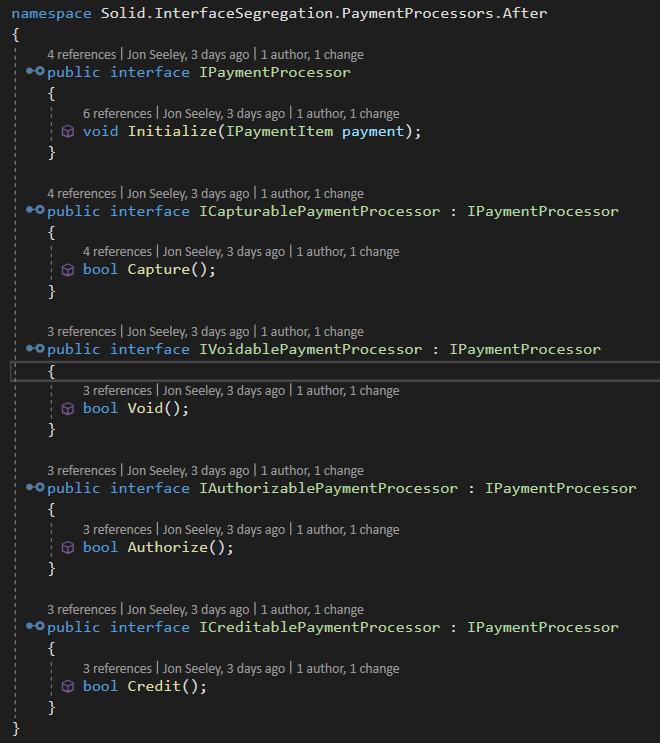

With that in mind then, let’s look at our “after” code and see how I’ve separated the interfaces out.

We no longer really need a base class for the processor so I start by removing that. Next, I set up a base IPaymentProcessor implementation that is simply used to Initialize any PaymentProcessor concrete implementation. Mileage may vary here. Where the meat of interface segregation principle comes into play, however, is as I separate each “action” into their own interfaces.

Our new interfaces are now: ICapturablePaymentProcessor, IVoidablePaymentProcessor, IAuthorizablePaymentProcessor, and ICreditablePaymentProcessor. Each one only exposes the interface specific to it’s purpose.

Putting it together

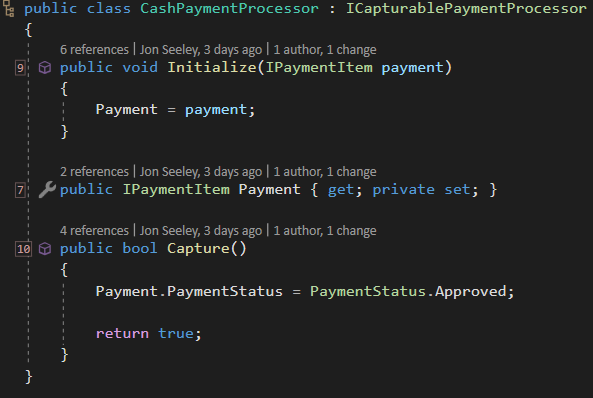

Now that we’ve broken it down we can move on to actually gluing it all back together. As I mentioned previously there really is no reason that my concrete classes need to be separated out. In the case of CashPaymentProcessor it only implements the ICapturablePaymentProcessor. CreditCardPaymentProcessor, on the other hand, implements all four.

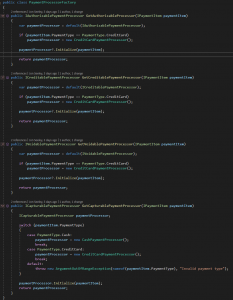

The PaymentProcessorFactory for the “after” section is pretty messy. In true production code you’d be using a DI framework and have some more fancy matching logic in place but for sake of the example I think it illustrates it well enough.

The test code in the console application attempts to load a payment processor for both cash and credit card payments for a specific action. I use the null conditional operator to run the method or simply return false if no instance is available.

Why is it “better”

So why? What makes this “better” than the “before” code approach? Take a look at our CashPaymentProcessor again. In the old way we had a bunch of unimplemented code. Somebody comes into our code later (might even be us) and we might not recall why those methods are not implemented. At best it is a huge code stink, at worst it’s a maintenance nightmare. Now that CashPaymentProcessor *only* implements the ICapturablePaymentProcessor it is quite evident what the purpose of that processor is. It only knows how to capture payments and we don’t expect it to have any other function at all. Thus, our code is now both cleaner and self-documenting.

Conclusion

Design principles help us organize clean and maintainable code. The Interface Segregation Principle states “no client should be forced to depend on methods it does not use”. This means no “NotImplementedExceptions” or empty method declarations. Implementing ISP does not preclude us from also implementing SRP.

Locate code for this post on my GitHub profile. I’ve split into two portions: before and after.

Photo Credits

Photo by Will Francis on Unsplash